This text is a part of a partnership between The Jersey Bee and Subsequent Metropolis to discover segregation in Essex County, New Jersey, and options to construct a extra honest and equitable county and state.

A small farm with large group worth in Montclair’s Third Ward.

Through the summer time, Montclair Neighborhood Farms transforms its lower than 10,000-square-foot area into an area with one thing for everybody: a backyard schooling program for kids, a job coaching area for youngsters and a pop-up produce marketplace for Essex. Resident of the county.

“Folks love residing right here,” mentioned Lana Mustafa, government director of Montclair Neighborhood Farms. “It is advanced into one thing actually stunning and productive and community-based.”

On a balmy afternoon in early June, bunches of lettuce, bok choy, parsley and garlic started to sprout and ripen. Some are even prepared to reap. Mustafa and his group put together stock for his or her Monday farmers market, the place dozens of consumers use their SNAP or WIC advantages to purchase recent produce.

Learn: The right way to apply for meals help and help in New Jersey

However Mustafa mentioned it isn’t straightforward to serve Essex County residents when governments do not contemplate city agriculture a viable resolution for bringing inexpensive, recent meals to food-insecure communities.

To do this, the state should confront its sophisticated farming historical past and pair it with long-term municipal funding — steps New Jersey has but to take.

“We want the state of New Jersey to take over city [agriculture] Severely,” mentioned Mustafa.

Time and time once more, Mustafa says, pink tape has hindered his skill to serve his small farm group. As a result of he does not have not less than 5 acres of land, his utility to affix the federal Senior Farmers Market Diet Program — which allows him to obtain meals vouchers from low-income seniors — was rejected 4 instances. The US Division of Agriculture authorized his utility in 2023 solely after intensive assist with different group teams.

The excessive price of permits (as much as $5,000 a yr) compelled him to finish his composting program this spring.

“What about this meals waste that we won’t settle for it? It has to return to the landfill,” mentioned Mustafa, whose farm collects greater than 8,000 kilos of meals waste a yr.

Emilio Panasky, co-founder and government director of the City Agriculture Cooperative, mentioned it is no coincidence that city farms situated round seven of Essex County’s meals deserts do not obtain municipal assist.

Learn: How Essex County is falling quick on meals entry (and how one can assist)

“Client meals entry displays our patterns of segregation on this nation, and it is a political in addition to an financial selection,” Panasci mentioned. “It is no accident that outdoors of some struggling small farms and pop-up markets in Newark’s South Ward, our neighborhood in Maplewood — high-quality, recent meals choices are uncommon — and so they come at a premium. or South Orange.”

A photograph of Montclair Neighborhood Farm’s backyard beds, storage shed and group gathering area. Lana Mustafa mentioned her farmers market has served tens to a whole lot of residents on federal meals help applications lately. Picture by Kimberly Izer

Isolation in agriculture

Though rising meals habits could be traced again to indigenous and black agricultural practices, it was New Jersey’s white farmers who benefited most from an agricultural economic system constructed on slavery.

Through the 1700s and 1800s, farmers within the “Backyard State” relied on slaves to herd and slaughter livestock, develop crops, preserve their pastures, and construct their farms. Even after slavery was abolished in New Jersey in 1866, white farmers created their very own share crops referred to as “cottages,” the place previously enslaved black folks would offer labor in change for shelter and crops.

in his guide Agriculture whereas black, Leah Penniman particulars what occurred subsequent for farmers of coloration after the passage of Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Act.

“City farmers of coloration take away particles, plant timber, plant vegetable beds, and create constructions for group gatherings,” Penniman writes of the rise of black and Latinx farmers to revitalize agricultural traditions within the Nineteen Sixties and Nineteen Seventies.

Nonetheless, the legacy of segregation persists. A 2022 report from Rutgers College confirmed that New Jersey’s city farms are inclined to cluster in areas with increased SNAP participation, the place residents usually tend to be black or Latinx. And in a county the place white folks make up lower than one-third of the inhabitants, they personal three-quarters of all city farms in Essex County, based on the 2022 U.S. Census of Agriculture.

Fallon Davies, chair of Black and Brown, Indigenous, Immigrant Farmers United (BIFU), says these disparities are “systemic by design”.

“We’ve got to grasp that the system was by no means designed for black and brown folks to outlive this lengthy. It was by no means designed for us to thrive, survive, have households and be these stunning land creatures.”

They clarify the dearth of assist for city farmers that focused blacks in Essex County and perpetuated segregation.

“New Jersey has not prioritized city agriculture, which might defend and feed black folks,” they mentioned.

Cultivation with out water on borrowed land

A number of miles away from Montclair Neighborhood Farm, Kevin Porter’s farm in Newark has skilled a few of the setbacks frequent to city farmers. For starters, he nonetheless lacks fundamental agricultural infrastructure – comparable to operating water.

Greater than a decade after establishing Rabbit Gap Farm, Porter remains to be making an attempt to supply a constant water provide to the town of Newark. For years, he needed to make calls from neighbors or ask the fireplace division to ship gallons of water.

“They’re unaware of the truth that we’re a facility,” mentioned Porter, a black farmer and Newark resident.

Porter and his associate co-founded Rabbit Gap Farms in 2013 via Newark’s Undertake-a-Lot program. At this time, Rabbit Gap Farm is a 6,000-square-foot group hub in Newark’s South Ward that provides natural schooling, wellness applications and cooking courses to Newark residents, with greater than half of its public faculty college students eligible free of charge or decreased lunch. .

Porter’s farm faces one other frequent problem: He does not personal his farmland. By way of Newark’s Undertake-a-Lot program, residents can use however not personal vacant heaps within the metropolis, no matter whether or not they are inclined to them.

BIFU’s Fallon Davis additionally has a farm in Newark, which is run by their youth schooling nonprofit, STEAM City. They mentioned Undertake-A-Lot is “a flawed system trigger [the city] They’ll take it at any time when they need.”

Each farmers are working with the Belief for Public Land to determine methods to purchase their heaps in Newark.

“If we work out methods to get folks to personal land, if we train folks methods to develop their very own meals, if we train folks methods to advocate for themselves, that alone will change our group and so they don’t desire that, “Davis Dr.

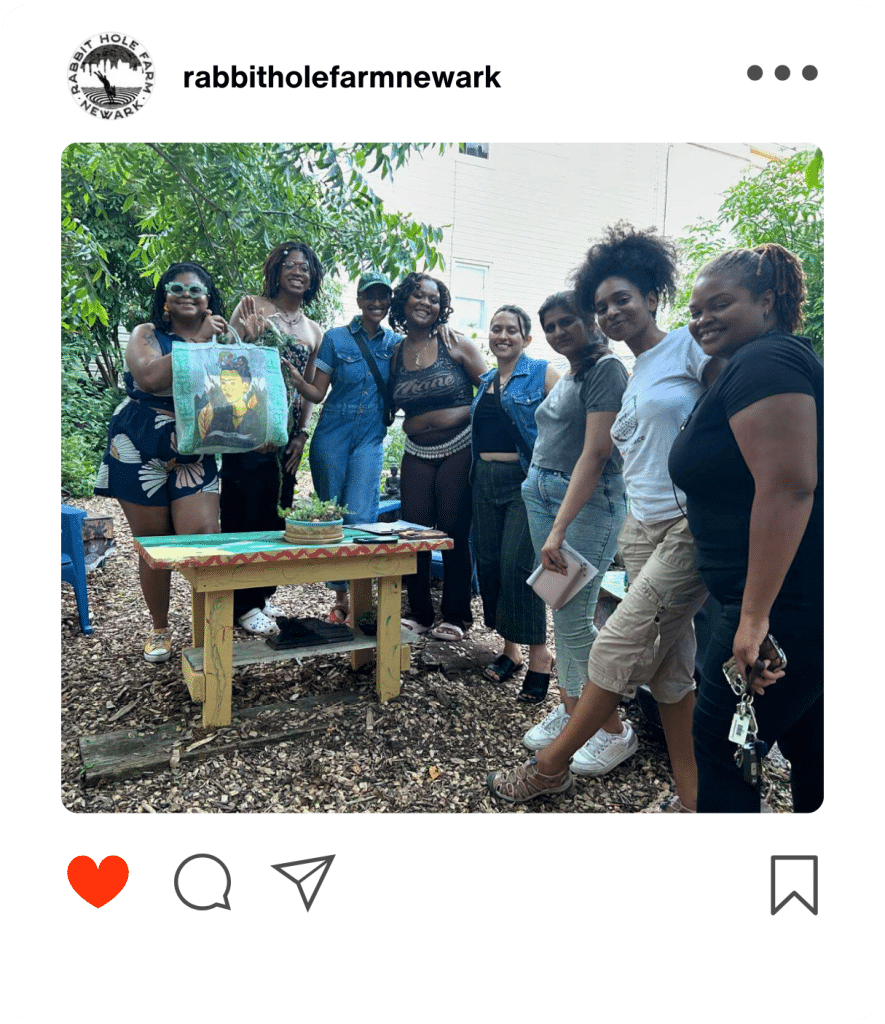

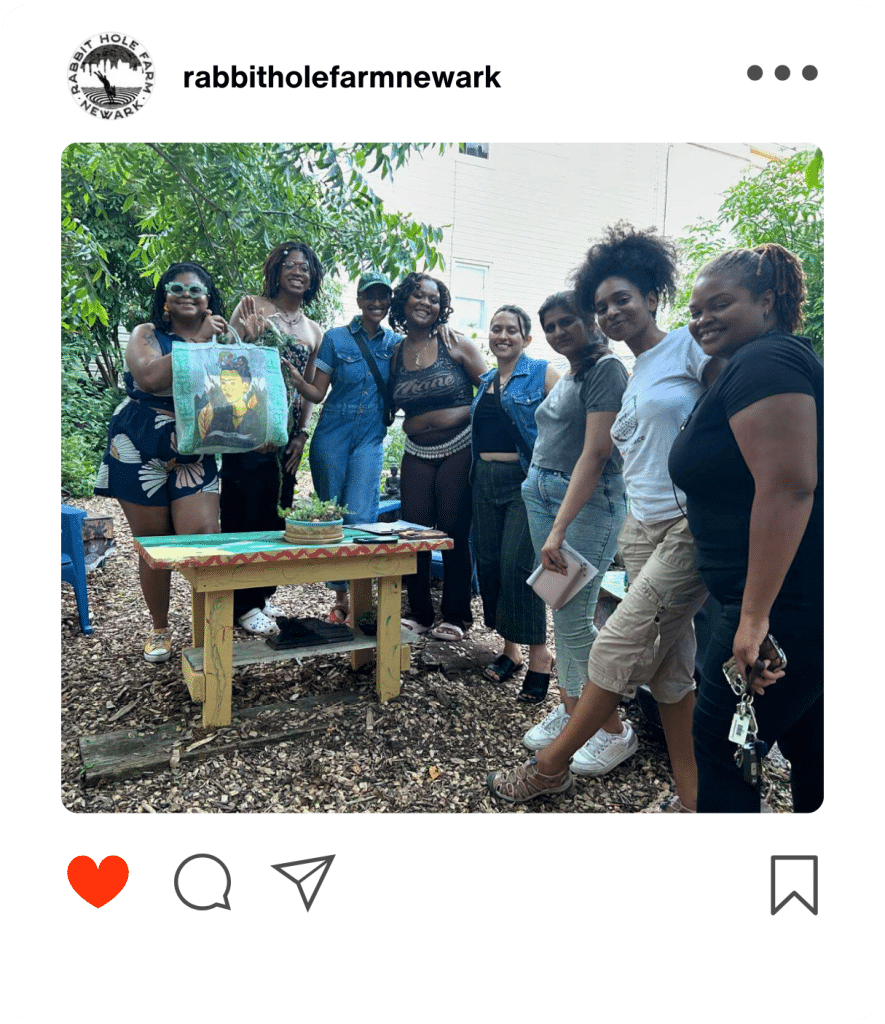

Herbalist Yaquana Williams hosted the Juneteenth Plant Exploration Class at Rabbit Gap Farm in June 2024. Picture from Rabbit Gap Farm’s Instagram.

Options targeted on permanence

Panasky of the City Agriculture Cooperative says long-term options that enable for meals rising in city environments and native meals markets are vital.

“Our zoning is totally different right here. Our focus is totally different. While you mix that with the truth that we lack an built-in city agriculture coverage on the native degree.. it is very troublesome for a farmer or farmer’s market to keep up land over time and … construct infrastructure on it,” Panasky mentioned.

On Fridays, Panasky and his group put together farm containers stuffed with kale, escarole, mushrooms, honey and eggs. His group collected information from greater than 30 growers throughout the state earlier than the group distributed the containers to colleges, meals pantries, hospitals and senior facilities with restricted entry to recent meals.

City Agriculture Cooperative staff put together household containers from his farm one afternoon in June 2024. Picture by Niki Villafon

Panasky emphasised that municipal assist is vital for city farms, that are particularly susceptible to gentrification and displacement from builders.

“Farming basically is tough, however city farming when there is no actual city system for it… it is virtually set as much as not work. [and] To essentially weaken you,” Panasky mentioned.

City Agriculture Cooperative distribution luggage are loaded right into a pickup truck at their warehouse in Irvington, NJ in June 2024. Picture by Niki Villafane

Up to now few years, a number of payments have been launched geared toward formalizing city agriculture insurance policies and sustaining the sector.

In January 2024, Assemblywoman Annette Quijano reintroduced a invoice to determine an city farming pilot program for rising city farms. Senator Teresa Ruiz and Senator Nellie Pau additionally reintroduced a invoice that might set up an city agriculture grant and mortgage program. Neither invoice made it out of committee for additional consideration.

Jeanine Cava, government director of the NJ Meals Democracy Collaborative, factors to the Massachusetts Wholesome Meals Incentive Program (HIP) as a potential mannequin for what’s potential in New Jersey. This state-funded program reimburses SNAP customers once they buy meals from eligible HIP distributors.

“Proper now, we do not have state funding particularly for incentives like this that encourage folks to purchase domestically grown meals,” he mentioned of the dearth of everlasting funding.

BIFU’s Davies emphasised that black and brown farmers should be on the middle of any city farming resolution. BIFU’s 40-member statewide consortium plans to launch their coverage decision later this summer time, which can embody suggestions on land possession and state funding for BIPOC farmers.

“We additionally must pay [politicians] We’ve got some language to ask… the group must do some work,” they mentioned. “If you wish to change your group, it’s a must to advocate in your group.”

Be taught extra

Be taught extra about upcoming applications and occasions at Montclair Neighborhood Farm and Rabbit Gap Farm.

You will get concerned with the City Agriculture Cooperative, Black and Brown, Indigenous, Immigrant Farmers United and the NJ Meals Democracy Collaborative via programming and advocacy alternatives.