Why pray alone or with your loved ones when you may pray with large celebrities on the Hey app? Why restrict your self to studying or listening to the Gospel when you may have a Jesus with all the fun and enchantment of a Netflix collection? Why develop Ignatian prayer expertise of lively creativeness when you may passively expertise an immersive demonstration that brings to life a storm on the Sea of Galilee?

Why would you be glad with an odd church when you may digitally tour Europe’s biggest cathedrals or take heed to well-known preachers within the consolation of your house? Or why accept conventional photos of Jesus or figures from the Bible and church historical past when photos of what the atlantic “Sizzling AI Jesus” and Sizzling AI Saints now increase on-line?

These are however a couple of of the questions raised by the dizzying acceleration of our digital age, and Christians have the very best solutions. Right here, I’ll give attention to synthetic intelligence renderings of Jesus and discover how the instance of Michelangelo, the best Christian artist in historical past, may help us resist the temptation of synthetic devotion.

The best response to AI Jesus is that the iconoclasts—the Christian icon-breakers who guarded towards or outright destroyed devotional photos in eighth-century Byzantium and sixteenth-century Europe—have lastly been vindicated. An AI-generated picture just like the Shrimp Jesus is definitely sufficient to make some hope that the fashionable equal of Oliver Cromwell’s stained glass – the shattered troopers will quickly trip once more.

Trendy iconoclasts would argue that church buildings ought to be plain and imageless, a much-needed weekly cleaning of our digitally fatigued visible palettes. That is venerable and historical recommendation. The fourth-century hermit father Evagrius of Pontus wrote, “If you pray, don’t think about the divinity as some picture shaped in your self. Keep away from permitting your soul to be affected by any explicit formed seal, however moderately, free of all matter, strategy the fabric being and you’ll perceive.” In different phrases, delete the app.

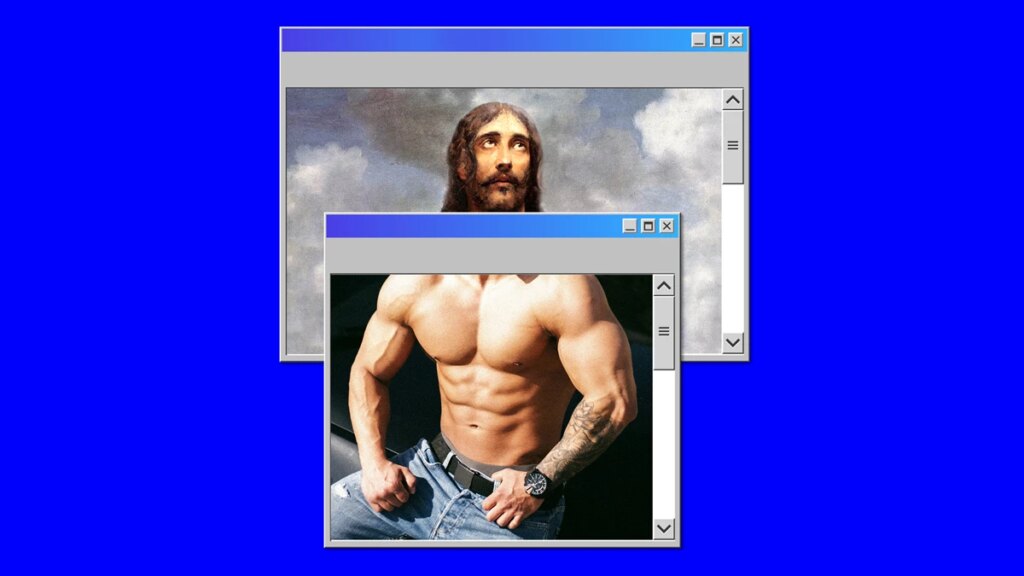

Picture: AI-generated picture by CT/Midjourney/Fb

CT created Sizzling AI Jesus (left) impressed by social media traits on Fb (proper).

One other reply—from an iconophile, or image-lover—would embrace these new developments wholeheartedly, channeling them into optimistic affect. Arguably, this was Michelangelo’s methodology. As his profession started, visually arresting classical sculptures had been excavated from the bottom, prompting many a disaster of religion: Did Christianity carry such visible splendor to a untimely finish?

Michelangelo’s early sculptures answered with a powerful no, displaying that Christian artwork could possibly be as lovely as that of the classical world, or much more so. Maybe, we should always take an identical strategy to the brand new medium of AI, each embracing and transcending what the world provides us at the moment.

I attempted that trick myself, spending months utilizing AI to resurrect a misplaced African saint in an AI-generated icon. It leaves me chilly. To be trustworthy, the complete embrace method left even Michelangelo chilly. “In order that the fond creativeness, which made Artwork to me an idol and sovereign,” he wrote in a sonnet of the late 1550s, “I now plainly see was laden with error, as males will despite their greatest pursuits.”

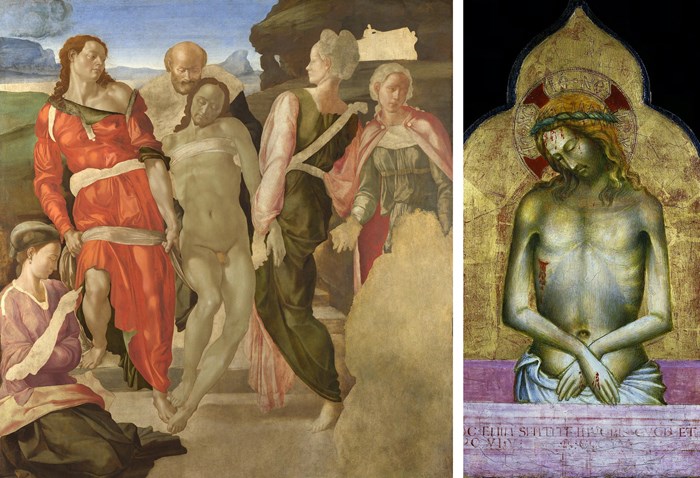

Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

Classical bust of Laocoön, found in 1506 and an instance of Michelangelo’s alluring Christian response, Cristo della Minerva (1519-1521).

However that disillusionment with cultural manufacturing doesn’t imply that the iconoclasts win the argument. Michelangelo didn’t surrender artwork solely. As an alternative he returned with renewed depth to a lifelong curiosity within the easy and pure aesthetics of historical Christian icons, which he tried to duplicate or echo at varied occasions. One artwork historian persuasively argues that Michelangelo’s objective was “to protect the custom of spiritual imagery at a time when creative developments threatened their integrity and dominance,” and this—I consider—ought to be our technique at the moment.

Michelangelo actively diminished the visible methods he had mastered. Influenced by the Reformation doctrine of grace, Michelangelo’s final works are intentionally impoverished. You possibly can see this modification within the distinction between his first and extra well-known compassionMade when he was in his early 20s, and Rondanini Pieta, was executed when he was in his 80s. Within the first, the larger-than-life, impossibly younger Mary holds Jesus; Within the intentionally tough and unfinished second, Jesus—even in his demise—appears to help the appropriately aged Mary.

Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

Michelangelo’s Entombment (1500-1501) and the Humble Historical Icon (1405) helped encourage it.

Michelangelo’s belief in historical, humble artwork types and willful embrace of visible poverty helped him navigate the turmoil of the sixteenth century, and it may well assist us navigate our personal. Seduced by AI’s flashy and sexually suggestive photos of Jesus, we will profit from the knowledge of devoted iconoclasts with out abandoning devotional photos altogether.

Like Michelangelo, we will select to create and ponder Christian photos which might be humble, maybe unrefined however intentional and devoted. We will search for artwork that doesn’t dazzle our earthly senses however leads us to heavenly realities. The present “knowledge units this [AI] The instruments which might be educated on are biased towards hotness,” new instruments are much less seemingly to assist We do higher to embrace photos that intensify their poverty, photos that say, like John the Baptist, “He should enhance, however I need to lower” (John 3:30, KJV).

Michelangelo’s instance teaches us to be suspicious of alleged visible grandeur. Even when machines can now create sculptures as he did, the lesson of Michelangelo’s final years stays the identical: Christian photos, as a lot as they deserve the title. christian, ought to be intentionally restrained, as a result of their goal is to not appeal to consideration or glory however to show our eyes to Christ. The standard canon of Orthodox icons, extra reasonably priced now than ever, nonetheless works remarkably properly.

Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

Michelangelo’s early Pietà (1498-99) and his late Rondanini Pietà (1564).

Confronted with its personal perplexing array of eloquent preachers and apparently absorbed pagan worship, the traditional church requested the questions with which I started. The apostle Paul’s reply was frank, even blunt: “I didn’t include eloquence or human knowledge as I declared to you the testimony of God,” he wrote to the Corinthian church. “For I resolved to know nothing whereas I used to be with you, besides Jesus Christ and Him crucified. I’ve come to you weak” (1 Cor. 2:1-3).

Between this and Michelangelo’s testimony, then, I see a easy rule for sifting by this new spherical of visible enchantment: by no means belief a picture or a savior with out wounds.

Matthew J. Milliner is professor of artwork historical past at Wheaton Faculty. He’s the newest author Mom of the Lamb: The Story of a International Icon.